This week Sonja and I got our ARCs, our Alien Resident Certificates, which allow us to re-enter Taiwan if we leave, open a bank account, and enroll in the national health insurance program–for the next six months, anyway. Or as a colleague put it, “Now you are a real person!”

Getting the ARC is a bit of a process. You need all sorts of documentation filled out and certified in just the right way by just the right people, and the time and patience to spend some hours at the immigration office. You also need to have come into the country originally on a resident visa, and acquiring a resident visa is itself a multilayered, multistep process. To get a resident visa, you need not only the usual stuff–your passport and other documents proving your identity and relationships to members of your family, a letter of appointment or enrollment from your Taiwanese employer or school–but also a recent health inspection, to include chest X-ray for tuberculosis, blood test for syphilis, and a blood test for measles and rubella immunity. For US citizens, the skin test for leprosy and the stool inspection for parasites are waived, but for citizens of many other countries, they’re not. And each of your documents has to be first notarized and then authenticated by TECO (Taipei Economic and Cultural Office).

An aside: TECO is the thing in the US that is definitely not (wink, wink) a consulate, since the US stopped recognizing Taiwan as a country in 1979. Just like AIT (American Institute in Taiwan) is the thing in Taiwan that is definitely not (wink, wink) an embassy. They’re just private nonprofit cultural-and-economic-exchange offices…that happen to issue visas, authenticate documents, and be staffed by diplomats who advocate for their citizens. Shh.

The TECO office shares with the Chinese consulates I’ve experienced a love of stamps and seals–this goes way back and is deeply embedded in East Asian societies. Check out this photo I took at Taiwan’s National Museum of the Japanese governor-general’s seal when Taiwan was a Japanese colony.

Now that’s a seal! But seals aren’t just a historical artifact in this part of the world. An American friend of mine used to work at the US consulate in Shanghai doing visa interviews for Chinese citizens who wanted to go to the US to study. She said she occasionally encountered fraudulent applications–that is, people who were falsely claiming to have been accepted or enrolled at a US institution. They were often easy to catch because the acceptance letters they brought in were festooned with seals the way an official letter from a Chinese institution would be; the applicant hadn’t realized that US universities don’t go in for stamps in the same way. They also tended to be on A4 paper instead of 8.5 x 11.

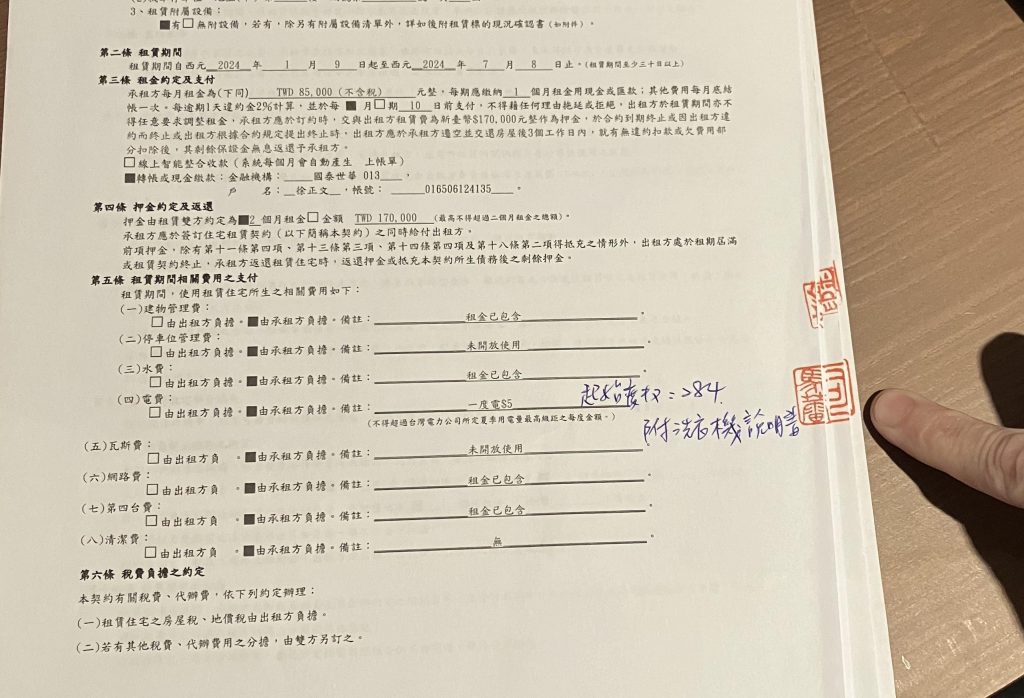

Today, pretty much every adult in Taiwan has their own seal that they use on official documents. Fulbright has one made for each of its grantees with their Chinese name; so far I’ve used mine on my apartment-rental contract and on the documents I signed to open a bank account. Oh, and Taiwanese citizens use them on their ballots when they vote! On election day the news channels kept reminding people to be sure to bring their ID and their seal to the polls with them.

So anyway, it’s no surprise that Taiwanese immigration authorities are in the seal-collecting business as well. Sonja’s birth certificate needed to be authenticated by the New York TECO office (stamp!) since Sonja was born in Pennsylvania, which is in TECO-NY’s jurisdiction. Our health certificates had to bear the official stamp of the hospital where the health inspections were done (stamp, stamp). Our passports and health certificates had to be authenticated by the Denver TECO office (stamp, stamp, stamp, stamp). And before TECO would authenticate any of those things, each one had to be notarized, as did the visa application forms (stamp, stamp, stamp, stamp, stamp, stamp, stamp).

I spent a lot of time with the friendly notary at our local bank before we left. The notarization requirement was a bit of a puzzle, actually. It’s pretty obvious how to notarize an application form: you take the unsigned form to the notary, show them your ID and then sign the form. Then the notary stamps the form indicating that the person who signed it is the person whose ID they saw. But how do you notarize a health inspection? Apparently I am not the only person mystified by this. A colleague of mine took her completed health forms to the notary and asked him to stamp them. They stared at each other awkwardly for a moment before he said, “Um, you have to do something in front of me so I can attest that you’re the person who did it.” But neither of them knew what action she was supposed to perform in front of him. Surely you’re not expected to have a notary accompany you to the lab to watch you get your blood drawn or your chest X-rayed (or worse, collect your stool sample)? In the end my colleague found a notary who was more lax with the stamps and it passed muster at TECO. I guess it’s one of those expectations that must be fulfilled in a pro forma way but that no one actually believes in much. Maybe a consulate pretending not to be one is disposed to overlook fudging in a way that a regular consulate wouldn’t be.

So anyway, having arrived in Taiwan with your resident visa, you might already feel like you’ve successfully jumped a long series of hurdles. But as soon as you enter the country the clock starts ticking: you have fifteen days from the time you enter to convert your visa into an Alien Resident Certificate. I’m not sure what happens if you miss that deadline, but I didn’t want to find out. But before you can apply for the ARC, you have to have a housing contract in hand, which means you need to find a place to live. So Sonja’s and my first week in Taiwan felt to me less like a grand adventure and more like a frantic hunt for housing. The time pressure I was under also helps explain how we ended up paying way more rent than I’d anticipated and living way farther away from Sonja’s school than I’d hoped–but that’s a story for another time. For now, suffice it to say that we managed to secure a housing contract in time to meet the ARC deadline, and thanks to a lot of guidance from the Fulbright staff and colleagues who’d gone before me, when I showed up at the immigration office I had the requisite documents properly filled out, sufficient copies of same, extra passport photos and cash, and thus managed (just barely) to clear the bar for a successful application. A mere two weeks later, I picked up the cards identifying us as government-approved aliens.

At this point, I want to acknowledge the chorus of teeny violins that readers who’ve dealt with US immigration bureaucracy must be vigorously playing. Oh, you poor visiting American who had to go to the notary all those times! How hard it must have been for you. At least, that’s what I’d be saying right now in your place. And it’s true: for me, this has been a time-consuming challenge but not something my future hinged on. And although I’ve experienced some confusion, unanswered emails/phone calls, and contradictory instructions, no one has been outright rude to me or made me feel like I am unwelcome in this country. At most, becoming a resident alien in Taiwan has given me a tiny taste of what must be the less-stressful aspects of attaining residency and citizenship in the US. So to all of you who’ve gone through or are going through that, my hat is off to you.

Congrats! Those seals are cool. Now I want one.