Talk given at Sunday Seminar, United Methodist Church, Denver CO, 26 Sep 2021

I have two things I’d like to talk about today. The main one is a book by historian and sociologist Steven Shapin called A Social History of Truth: Civility and Science in Seventeenth-Century England [Bookshop.org, WorldCat]. It looks at the early history of the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge—the oldest national scientific society in the world—and how its members could decide what counted as legitimate testimony about natural phenomena. What sort of evidence or testimony, by whom, could be credited as true, and how could such matters of fact be discussed while preserving the social harmony necessary for the Society—and society at large—to continue? Shapin’s book was published in 1994, so it’s not new. And, so far as I know, it is little-known beyond scholars interested in the history of science. But it concerns the origins of what we today call science—Shapin and many others argue that we can see in 17th century England the early forms of the scientific laboratory, experimental research, and scientific modes of discourse that in many ways still pertain today.

Second, I think the book gives a good introduction to theories about the social construction of scientific knowledge, the development of which is my second topic. I think many of us have at least a passing familiarity with ideas from the philosophy of science that set science apart as a special form of knowledge—developed from observation and experiment, reproducible, falsifiable, with hypotheses rigorously tested and reviewed, and theories proposed and rejected based on the available evidence. But what does it mean to say that scientific knowledge is “socially constructed”? Who developed these ideas, and why? Does saying that scientific knowledge is socially constructed mean that there is no objective reality, and that potentially anything could be regarded as ‘true’?

So: I want to use Shapin’s book to put the early development of science into its historical context, and I want to put Shapin’s book in the context of the history of the sociology of science, and maybe we can think together about what all this might mean for our current political and cultural moment.

Here is the book that will be our jumping-off point: A Social History of Truth: Civility and Science in 17th-Century England, and on the left is the author, Steven Shapin. Like many eminent historians of science, Shapin started out as a scientist. He studied biology as an undergraduate, and did some genetics research as a graduate student. But he switched fields and in 1971 earned one of the first (if not the first) PhDs awarded by the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of History and Sociology of Science, where Hilary also earned her PhD in 2008, and where I had a mostly pleasant six-year interlude between forms of remunerative employment.

As Shapin notes in his introduction, a social history of truth is not supposed to be possible. Truth is supposed to exist outside of ourselves—a thing beyond us that we seek, not something that a group of people can develop or decide among themselves. It is not something contingent on the social dynamics of the group, their politics, their positions in society, and their (almost assuredly somewhat flawed) assumptions about how the world works or should work. But how do you decide what is true? How do you know whether or not to trust that something you witness, or something you are told about the world, is true, and actually tells you something about that objective Truth out there? Those are some of the questions the fellows of the Royal Society faced as they questioned the reality of things that had long been regarded as true, and sought to develop new, more authentic, knowledge for themselves and for the rest of the world.

I will be using some terms here that might need some explanation. I’m talking about the history of science, and scientists, but those terms were not in use in the 17th century. ‘Science’ and ’scientist’ don’t come into widespread use until well into the 19th century. The terms more likely to be used in the 17th century were “natural knowledge” for the knowledge being produced and “natural philosophers” for the people doing the experiments. The term “natural philosophy” itself first came into use in the 1500s—denoting what its practitioners saw as the emergence of a new, specialized, form of philosophy.

Shapin’s focus in the book is on this man, Robert Boyle. You might recognize the name from “Boyle’s Law” of the relationship between pressure and volume of a gas. In fact he never described that relationship as a law, and never formulated it as an equation—and there are some interesting reasons why he didn’t, which we will get to in a bit. He is regarded today as one of the founders of modern chemistry, but like many “natural philosophers” of his day, he was interested in a lot of things, and also wrote about theology, physics, medicine, and other topics. Together with like-minded compatriots such as architect Christopher Wren and Anglican clergyman John Wilkins, he was one of the founding members what would become the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge. The group started as an informal meeting of friends in 1660, and a few years later received its first Royal Charter. It conducted meetings where its fellows would discuss topics of natural knowledge; it sponsored experiments that were conducted before its members; it operated an extensive correspondence network, connecting natural philosophers across Europe; and in 1665 it began publishing its “Philosophical Transactions,” which were hugely important in spreading news of discoveries across the Western world.

Boyle was widely regarded in his time as the exemplar of the natural philosopher—someone whose word on matters of fact could always be credited. Shapin argues that Boyle was vital in the process of inventing that role, and in developing modes of self-presentation and conduct that helped allow for debate among such philosophical gentlemen without leading to discord and ruptures in the social fabric of the Society, and the larger community of natural philosophers across Europe.

Let me zoom out a bit to look at the context of Boyle’s life to talk about why Boyle and others thought there was a need for natural philosophers, and why they might have been especially concerned with maintaining social harmony. There were a lot of things happening during Boyle’s lifetime. Firstly, there is the incredible intellectual ferment that will later become known as the Scientific Revolution, which is usually dated from 1543, when Nicolaus Copernicus published his thesis that the sun, not the earth, was at the center of the solar system, to 1690, shortly after Isaac Newton published his Principia, which formulated universal laws of motion and gravitation.

The causes of the scientific revolution are complex and hotly debated—reasons as varied as the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, or the Protestant Reformation, or the invention of double-entry bookkeeping, have been posited as motive factors in its development. But regardless of its causes, what was motivating Boyle and his contemporaries was a palpable feeling, as new lands were discovered overseas, and new worlds viewed through telescopes and microscopes, that the traditional sources of authoritative knowledge were no longer adequate to explain the world around them, and that new knowledge—and new methods of gaining knowledge—were needed. Moreover, they thought, this new knowledge should have a different character than the text-based knowledge of the scholastics and tradition-bound monkish scholars. The new research would be focused on “useful knowledge” that allowed people to do new things and live better lives. It would also be public knowledge—not hidden away in the occult laboratories of alchemists or kept as the trade secrets of craftsmen. The new natural philosophers couldn’t take the word of old texts—they would have to rely on their own senses, and experiment with phenomena to find out how the world really worked. And the knowledge they gained would be openly debated and widely shared, for the benefit of all mankind.

This was also an economically and socially turbulent time. Discoveries in the New World and an increase in trade helped create a new wealthy merchant class, and financial and legal tools such as the corporation and stock market fueled the growth of capitalist enterprise.

There was a lot of political and religious unrest as well, as you can see from the red-tinted events on this timeline. Most seriously, civil war broke out in England in 1642. In 1649 King Charles I was beheaded, and for a decade England was ruled by a “rump parliament” and Oliver Cromwell’s military dictatorship. In 1660, Charles II was restored to the throne, and the political chaos finally began to subside.

Against this backdrop of economic, political, social, and intellectual change, the Royal Society was founded in 1660—the same year Charles II regained the throne. Its motto, in keeping with the idea that new knowledge and new methods of gaining knowledge were needed was Nullius in verba—“take nobody’s word for it”—reflecting the skepticism with which its fellows were supposed to approach the world. They were supposed to witness things themselves, not just take the word of others or accept at face value reports of experimental results from elsewhere. Practically speaking, though, this type of skepticism had its limits. It was obviously not practical (or sociable) to doubt everything you heard from others. You had to rely on the word of others in many instances in order to rebuild to stock of knowledge. So trust was a vital element in gaining new knowledge, and there had to be some criteria—some set of formal and informal signs—that could guide you in discerning the trustworthy from the unreliable. In the case of disagreement about particular claims, there also had to be a way to debate them without causing offense, and potentially disrupting the community of knowledge-makers. Shapin goes into great detail in explaining how Boyle and his contemporaries developed those criteria, and how they used them to bolster the credibility of their own claims. Like most, if not all, inventions, these criteria were not wholly new, but rather were adapted from preexisting ideas about trustworthiness, courtesy, and how conflicting claims might be adjudicated.

So, who could you trust to supply testimony about things you yourself had not witnessed? Well, first and foremost the person should be a Gentleman. Shapin delves deeply into 17th-century courtesy books—basically manuals or etiquette guides explaining how to be a gentleman—to explicate the characteristics of a gentleman. What the 17th Century looked for in a gentleman was partly a product of earlier codes of chivalry and honor, over-laid with newer ideas of Christian piety. Here is my own distillation of the important points.

First and foremost, a gentleman had money. How much money? According to Shapin’s reading of the courtesy books, an income of 400 pounds a year was a minimum. More, obviously, was better. For comparison, at this time a well-paid tradesman might make 50 pounds a year, and a laborer or domestic servant less than 10. Boyle’s father was a self-made man, who gained a great deal of wealth as a rather ruthless expropriator of lands in Ireland. He made enough to essentially buy himself into a title, and he was made 1st Earl of Cork in 1620. He passed enough of his wealth on to Robert Boyle, his seventh son, so that Robert’s annual income greatly exceeded the gentlemanly minimum. The point was not that wealth equalled virtue, but that having enough money gave you liberty to do as you pleased, without having to worry about pleasing an employer or creditor, chiseling your customers in trade, or—God forbid—working with your hands to earn money, all of which were corrupting of the soul and mind.

Second, a gentleman was ideally an aristocrat, or if not actually ennobled, was well brought up in polite society, and well-educated. Robert Boyle himself did not inherit any titles, but he exhibited enough of the characteristics of good breeding that his standing wasn’t harmed. But there was this idea that the qualities of a gentleman could be carried in the blood, and that the longer the bloodline the more likely those qualities were to be refined or sharpened. In fact, as sort of an aside, after reading about experiments with blood transfusions, Boyle wondered whether a transfusion of blood could alter the temperament of the recipient, perhaps making a “fierce” dog “cowardly,” even perhaps transferring skills learned by one dog into the other.

And, when the Royal Society decided to perform an experiment transfusing blood from a sheep into a human, they found the ideal subject in a young man named Arthur Coga, who was indigent (and thus willing to do the experiment in exchange for 20 shillings) and probably a bit mad (so maybe the experiment would help him?). But, his description of the experience could be credited because he had been educated at Cambridge. He survived the experiment, and then wrote his description of it in Latin. Unfortunately—or maybe fortunately for him—he spent his 20 shillings on drink, and was deemed too debauched for further experiments.

In addition to wealth, breeding and education, a gentleman could also be expected to be honest—and an English gentleman especially so. In fact, a gentleman’s reputation for honesty might have been the most important part of his honor. The idea that “a gentleman’s word was his bond” goes back to secular codes of Chivalry, and in Boyle’s time it was reinforced by ideas from Christian morality. Shapin calls it a “truth culture” that prevailed in gentle society, and a reputation for dishonesty could be very detrimental to one’s social standing. In fact, one of the gravest insults to a gentleman’s honor would be to accuse him of lying, or to “give him the lie.” The result, even though Christian moralists campaigned against it, could well be a duel to settle the matter. English gentlemen were supposed to be especially honest (or so said the English), because they were more plain-spoken than the gentlemen of the continent, and less likely to fawn and flatter than, say, the Italians for French.

The gentleman (though of course a good Christian) was also a man of the world—frequently seen in society, and welcoming of visits from other gentlemen. He was good company, not likely to cause a scene or give offense at parties, and a good host.

Finally, his breeding, education, and politeness instilled in him (and were signs of) a stability of character and firm self-control. He was not likely to be carried away by his or someone else’s emotions, and had sufficient command of his faculties to know when reason should temper sense, or when sense experience might have precedence over reason.

All of these things combined to make the gentleman a free actor, cable of giving his assent to matters of fact, or not, according to his own volition, and not beholden to anyone else or to his baser instincts (such as greed or ambition) or emotions in his reasoning and testimony.

These qualities were also recognized by the English legal system, so that the testimony in court of a gentleman was given greater weight than that a commoner. In this as in other respects, the originators of the role of natural philosopher were borrowing and adapting for their own purposes from pre-existing social codes and procedures.

In addition to the qualities of a gentleman, Boyle could also call upon his reputation as a good Christian to bolster the credibility of his natural philosophy. It also helped him temper some of the inconvenient expectations of him as a gentleman. He was somewhat frail in health, may have suffered from a speech impediment, and was fairly private—all things that conflicted with the bonhomie expected of a gentleman. He also portrayed himself in his writings as pious and simple in his ways and religiosity. This naturally made him more trustworthy, but his monkishness could also be used to excuse himself from the social obligations that would accrue to a less ostentatiously pious gentleman.

How were these criteria put to use in the Royal Society in determining what would count as valid testimony about matters of fact? The characteristics of ‘gentlemanliness’ described above were not formal criteria for membership in the Royal Society. They were more informal conventions that Shapin has teased out through his examination of courtesy books, and the writings of Boyle and other Royal Society members. In fact, membership in the Royal Society was theoretically open to persons of any social standing. And one of its outstanding members was Robert Hooke, who was actually an employee of Boyle and the Society, as one of Boyle’s laboratory assistants and the Society’s ‘curator of experiments.’ But in practice its fellows were predominantly gentleman. And while it prized public knowledge, it’s not like they had public galleries where just anyone could attend the experiments and debates. Members and invited guests, and those attending virtually via the Society’s published accounts of the meetings, constituted the “public” the Society was addressing.

Just as the practical “public” of the Society was a bit more complicated than the Society’s rhetoric might have made it seem, so was the presentation of the experiments and debates over ‘matters of fact.’ The rhetoric of the natural philosophers emphasized first-person witnessing, and the Society indeed had experiments performed before its members. Boyle’s descriptions of his experiments emphasized his own simplicity, and used common language to relate what happened during the experiment. The descriptions were intentionally verbose, and described even accidents—like the apparatus breaking—during the experiment. It was meant to be a form of ‘virtual witnessing’ that gave greater credibility to his accounts. But Shapin shows (in this book and more extensively in other publications) that in fact the process of performing an experiment involved a fair amount of stage managing.

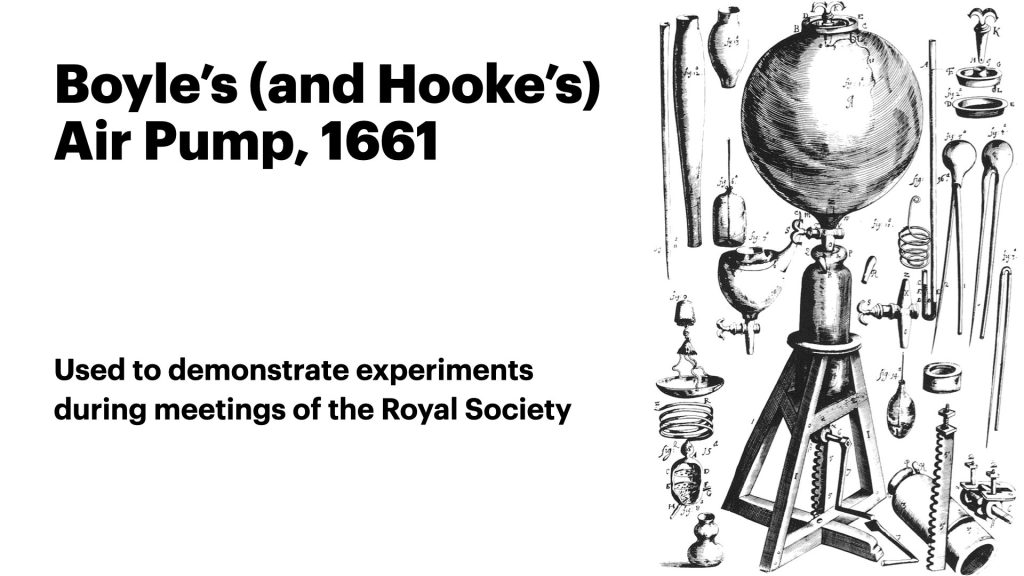

Some of Boyle’s most famous experiments were with the Air Pump, a device built by Robert Hooke (possibly of his own design, possibly on the instructions of Boyle). The device worked by cranking the handle, which would draw a piston down inside the metal flask there in the middle, and that would in turn suck the air out of the glass bulb at the top. An opening at the top allowed experimental subjects—like candles or small animals—to be placed into the bulb, so you could see what happened to them when the air was exhausted from the bulb.

This is the second version of the air pump. It’s kind of hard to see, but there is a very surprised-looking animal—probably a rat—inside the glass bulb.

Operating the air pump was tricky. Often the seals on the piston failed or some other air leak sprang up. Robert Hooke, as custodian of experiments, was tasked with preparing the experiments in the society’s workshop. When the apparatus was ready, it would be taken to the Society’s meeting rooms to be demonstrated during a meeting. Often the apparatus failed to perform as expected during the meeting, and something like “experiment failed to work” would be entered in the minutes, and Hooke would be asked to return the apparatus to the workshop and get it working correctly before it was presented at another meeting. Thus the presentation of experiments was not simple witnessing of a natural event. Instead, it was more a managed presentation of an event, the interpretation of which involved perceptions of the reliability of the apparatus, the skill of the person operating it, and preconceptions about how the experiment would turn out.

They did, however, insist that experiments be completed, and this contrasted with some Continental practices, where sometimes “thought experiments” would be described as if they had actually been done. If an experimental account lacked the specificity and concrete detail common in the Society’s accounts, for example, it could inspire doubt that the experiment has actually been done. For example, when word came from the French natural philosopher Blaise Pascal about some hydrostatic experiments that he had made, such as the one pictured here, Boyle doubted that the experiment had actually been performed, asking how the man pictured was able to sit fifteen or twenty feet below the water, as Pascal claimed, or how, with the man in that position, Pascal was able observe the effects at the bottom of the tube that were reported. Whether or not Pascal did the experiments or not, his accounts lack of circumstantial detail detracted from its credibility at the Royal Society.

Suppose there was some disagreement about matters of fact among natural philosophers? As I mentioned previously, accusing a gentleman of lying was a grave insult to his honor, and could potentially lead to a situation like that pictured here—a duel that took place in 1731 between two English political figures. A duel, of course, was extreme, and I don’t know of any case in the history of the Royal Society where a dispute resulted in physical combat. But a natural philosopher’s honor was still bound up in his observational reports, and to say that he perceived things wrongly was potentially damaging to his reputation and to the comity of the community of natural philosophers. So direct confrontation or contradiction was to be avoided if at all possible. In fact, Shapin notes, it was rare in meetings of the Royal Society that anyone’s reports of matters of fact were challenged. But if a disagreement had to be worked out, there were elements of the natural philosopher personae that could help smooth things over. These characteristics fit well with a gentleman’s general pose of humility and simplicity before experimental results, but it was also the result of a knowledge of the difficulties of experimental work and the variability of natural substances and phenomena, and a pragmatism born of the need to keep working together even if disputes arose.

Shapin describes an example of some of these dynamics at work in a dispute between two eminent astronomers—Johannes Hevelius, in what is now the city of Gdansk, Poland, and Adrian Auzout, in Paris—and the path of a comet (or comets) seen in 1665. A comet had been observed by many astronomers in late 1664 and followed until it faded in March of 1665. Then what was apparently another comet appeared that same month. There was a good deal of variation in the reported positions of the comet, but opinion gradually solidified around the idea that these two comets were in fact one comet. But Hevelius reported seeing the comet in positions in mid-February that disagreed with Auzout’s, and others’, observations. The track that I have marked in red here shows the observations Hevelius made that did not agree with the others. Both were well-known astronomers, and well-known for their accuracy. Even though Hevelius was the last major astronomer to not use a telescope for his observations (you can see him here with his wife making observations using a large sextant), he was known to have remarkably good eyesight, and had built himself the best instruments available for naked-eye astronomy. Hevelius had been elected a member of the Royal Society in 1664, and Auzout became a member in 1666. Hevelius reported seeing the comet in a different position than Auzout and other astronomers, and so the Society was put in the difficult position of having to choose between the observations of two of its members.

The first part of resolving disputes like this was what Shapin calls “probabilistic thinking” about phenomena. The members of the Society knew the difficulties of doing experiments and making accurate observations, and they were firmly convinced that specific locales and substances might vary considerably in their properties. Thus they never expected complete agreement among observers, and would reject the very idea of absolute certainty about natural phenomena. This was not only the pragmatic result of experience, but it also left room for resolving observational discrepancies without impugning a fellow philosopher’s honesty or competence.

In fact, for Boyle and his compatriots, exactness in measurement—a complete agreement between two observers or between theoretical prediction and results—tended to make a report more suspect, not more trustworthy. Boyle and philosophers like him knew that experiments and observations were messy, and so they expected only reasonable agreement, or as Shapin says “moral certainty” that a report was correct. Absolute certainty smacked of arrogance, which was very ungentlemanly, and it was impractical to expect from an imperfect world.

This is why Boyle would have never formulated “Boyle’s Law,” despite having collected the data to describe it and writing about the relationship between volume and pressure. First because Boyle believed in describing things in plain language, and he thought mathematics too abstract. Even though he himself was probably quite skilled at math, his writings always portray himself as a non-mathematician. More importantly, the very idea of a “natural law” was suspect for Boyle, as it neglected the importance of local circumstances, and was more an idealization and abstraction. This is also why mathematical calculation of natural phenomena was not highly valued by Boyle. Math was too abstract, and its expectations of exactness left no room for the particulars of a real-world situation.

As Shapin says, Boyle agreed with Francis Bacon that “Just because of mathematicians’ ‘daintiness and pride’ and their insistence upon abstraction, idealization, and absolute certainty, mathematics might be allowed a valued auxiliary role in philosophy but must never be permitted to ‘domineer over Physic.’ Mathematical expectations, canons, and forms of discourse were judged unseemly with the conversation of an experimental community.”

Shapin does not go into this, but I am guessing that this attitude was changing, or certainly must have changed after Newton’s Principia. But I do know that British education emphasized mixed mathematics—that is, math applied to mechanical systems—into the 19th century, and that even in the field of electromagnetism into the 20th century, British physicists used mechanical models alongside sophisticated mathematics to understand and explain their theories. So perhaps these are remnants of the early Baconian suspicion of abstraction and idealization.

But now back to the comet dispute between Hevelius and Azout. The problem with their disagreement was that Hevelius’s observations were too different from everybody else’s, and there just wasn’t any way to reconcile them by appealing to common observational variability. Moreover, neither party was being very cooperative in altering or withdrawing their claims. The solution was to revive the existence of two comets instead of one, and to leave the matter unresolved any further than that. This seemed to grudgingly satisfy both Hevelius and Azout, and when Hevelius published another account of the comet in 1668, he gracefully left out the observations that did not agree with Azout’s. And, though this face-saving solution might seem unsatisfying, it has endured: Shapin notes that since neither of the comets of 1664 or 1665 have yet returned, their “proper” positions cannot be recalculated. So today both are still in astronomers’ books—though for some reason both are now named after Hevelius.

Besides a pragmatic understanding the difficulties of experiment and observation, what is on display here is also a pragmatic attitude toward the goal of developing new knowledge.

As Shapin concludes, “The toleration of a degree of moral uncertainty is a condition for the collective production of any future moral certainty. This toleration allows truth-producing conversations to be continued tomorrow, by a community of practitioners able and willing to work with and to rely upon each other.” In other words, the philosophers of the Royal Society weren’t going to lose the forest for the trees. They needed each other for an important common endeavor. To be pedantic about a comparatively small point like the position of a comet or some other phenomena would be impractical. And, even, ungentlemanly.

I hope from this précis of Shapin’s book, you have gained an appreciation of Shapin’s argument, and have seen some examples of the following tenets of the social construction of knowledge, at least in the context of the early Royal Society. (And I should note that these are the main ideas that I hope I have communicated—not the main ideas that Shapin might have wanted you to get from his book.) The first is that as Shapin puts it, “thing-knowledge” requires “people-knowledge.” No report that reached the Royal Society could be evaluated apart from the identity of the person reporting it. A complex system of behaviors and signs operated in decisions about whose word you could trust. Second is that, though the Society’s rhetoric emphasized simple witnessing of phenomena, in practice it took a good deal of work, and often many tries, before Society members believed they had witnessed an authentic demonstration of a matter of fact. Similarly, observational reports could not be expected to agree completely, and the certainty that something had occurred, or that something had happened in a particular position, was never absolute. There was a process of debate and reconciliation about matters of fact, not just a single moment of “discovery.” As matters of fact gained currency—as they were debated, repeated and used in further research by other natural philosophers—they solidified as accepted knowledge. Only then might they lose their association with the persons, time and place of their initial production. Finally, I hope you have seen how the production of facts is a social process—one that involves not just individual “discoverers” and their reputations, but also technology (such as the air pump), organizations, and the culture surrounding the production process. The matters of fact reported by the Royal Society circulated as well as they did because of the reputation and power of the society’s members, the resources the society could pour into labs and apparatus, and because of the gentlemanly modes of conduct that allowed the community of philosophers to function, even in the face of occasional disagreements.

So, okay: Now we know something about the early history of science and the natural philosophers of 17th-century England. Does this have any bearing on our lives today? That, of course, is first of all for you yourself to say. But Shapin offers two of his own reasons. Science today is, for most of us, not a matter of personal, face-to-face relations as it was for Robert Boyle and his friends. Today we place our trust (or not, as the case may be) in large institutions and the professional strictures of scientific careers. Instead of trusting free actors, we are reassured about the honesty of modern scientific reports because of the rules and regulations that govern the conduct scientific research. But, Shapin argues, individual communities of scientists—the specialists in one particular field, for example—do still operate largely with face-to-face interactions. And many of the same rules of conduct and people-knowledge still pertain in the conduct of scientific research, even if they do not appear to apply to our own evaluation of scientific conclusions from the outside looking in. Second, Shapin believes that the necessity for trust is not just a characteristic of knowledge-making communities, but that it is a necessity for any community, even our society as a whole. Hence every group—even this one—must have some commonly understood rules governing its social interactions and the economy of trust—the moral economy—that makes it work. Shapin believes he is describing not just a particular situation in 17th-century England, but rather some general laws of societies in general. What would Robert Boyle think about that?

Finally, I promised you that I would try to put Shapin’s book in the context of the history of the sociology of science. This will be rather brief, both because I haven’t left myself much time, and because I don’t really have much intellectual warrant for discussing this. But here is my short story about the development of the sociology of science, at least as it is known here in the US.

It starts with Robert Merton, who in 1938 published an enlarged version of his PhD thesis titled Science, Technology and Society in 17th-Century England. This work posited what became known as the Merton thesis, that the spread of Protestant values in 17th-century England helped foster the growth of scientific knowledge. The reasons for this, Merton said, was a synergy between some Protestant values and those of modern science. He is also known for describing the Mertonian Norms of science, namely: communism, universalism, disinteredness, and organized skepticism. You can kind of see some resonance between those norms and some of the values Shapin describes among the fellows of the Royal Society, but as far as I know Merton’s ideas don’t currently inspire much research in the sociology of science.

The next guy in my little pantheon is someone you probably have heard of before: the philosopher Thomas Kuhn, whose 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions was a smash hit, as such books go. It introduced the concept of scientific paradigms, and described the progress of science as jumping along in paradigm shifts, rather than gradually improving as theories were proposed and rationally supported or rejected based on the available evidence. You will note that Kuhn was a philosopher, not a historian or sociologist. The philosophy of science was then dominated by the ideas of the Karl Popper and the positivists, who held that science was a special form of knowledge because its claims could be falsified. Popper and other positivists really disliked Kuhn’s ideas, believing that it made science out to be less of a rational endeavor than they felt it was. Kuhn’s ideas about paradigms and normal science are, I think, pretty influential. It was certainly the case that when I was in graduate school, I was expected to read and discuss The Structure of Scientific Revolutions on more than one occasion. I read Merton’s book once, I think, as part of a “forgotten classics” seminar, along with Max Weber and Marx.

Kuhn’s central insight was that maybe the philosophy of science would be improved if, instead of arguing over idealizations of scientific argument, we looked at the history of what actual scientists had done, and how they had assimilated, or not, new information about the world into their theories, which is something Boyle and the early Royal Society might have approved of.

If Popper and the positivists weren’t pleased with Kuhn’s ideas, neither was Kuhn pleased with what other people did with his ideas. He disdained the portrayal of science as irrational—which he thought was a misinterpretation of his ideas—and what he saw as an indiscriminate use of the term paradigm.

Next, we’re up to the present day—though since I have been out of touch with academia for many years now, some new theoretical approach that I am unaware of may be gaining steam in graduate seminars. I had a hard time figuring out who to put on the left here. I might have chosen Steve Shapin, but you’ve already been introduced to him, and his ideas are not really associated with a particular theoretical or methodological approach. I choose David Bloor because of his role in promoting what is known as the Strong Program in the sociology of science. Where Merton and Kuhn hated the idea of relativism, the Strong Program embraces it, at least as a principle of historical and sociological inquiry. Bloor describes the approach of the Strong Program as consisting of four main tenets:

- It is causal: it examines the conditions (psychological, social, and cultural) that bring about claims to a certain kind of knowledge.

- It is impartial with respect to truth and falsity, rationality or irrationality, success or failure of the knowledge claim.

- It is symmetrical: the same types of explanation are necessary for true and false beliefs.

- It is reflexivity: its patterns of explanation must be applicable to sociology itself.

And finally we have the French sociologist Bruno Latour. His work in developing what is known as Actor-Network theory (or ANT) has also been very influential, though when I was in graduate school it was regarded as something of a far-out avant-garde. ANT does, I think, embrace the spirit of the Strong Program’s four tenets, but it greatly broadens the field in terms of subjects of study. For actor-network theory, anything involved in the production of a knowledge claim is an actor in the network, and should be regarded as having just as much freedom of action as any other. So, for example, a lab tech can be an ‘actant. Or a computer. Or a test tube. Or a lab animal. It is the persuading of all these actants, from organism under study to the petri dish to the scientist to the lab’s organization to the government, to participate in the production of ‘matters of fact’ that makes new knowledge.

These scholars have been, within the sociology of science anyway, very influential. But the sociology of science is still a tiny field, so its overall influence should not be exaggerated.

That’s one of the reasons why the “Science Wars” of the 1990s seem so strange to me. If you do not recall the Science Wars, it was (in my opinion) a collective freak-out among some scientists about what they saw as the growing influence of French post-modernism. Given that the influence of post-modernism was hardly ever felt outside of English departments, and that even if all the English departments in all of the world unanimously decided science was just a word game, it probably wouldn’t make one bit of difference to any of the science departments, this high-profile fretting over the status of science seemed to me at the time as pretty puzzling. In retrospect, with a fair part of the more rural and conservative right claiming that global warming doesn’t exist and that COVID-19 is a hoax—or treatable with horse dewormer if not—the idea that the greatest threat to scientific authority was the academic left seems positively laughable. But in any case, the sociology of science—especially the Strong Program and Actor-Network theory, got caught in the post-modernist net of these concerned scientists, and the relativism sociologists of science were said to be promoting was identified as part of this grave threat to science.

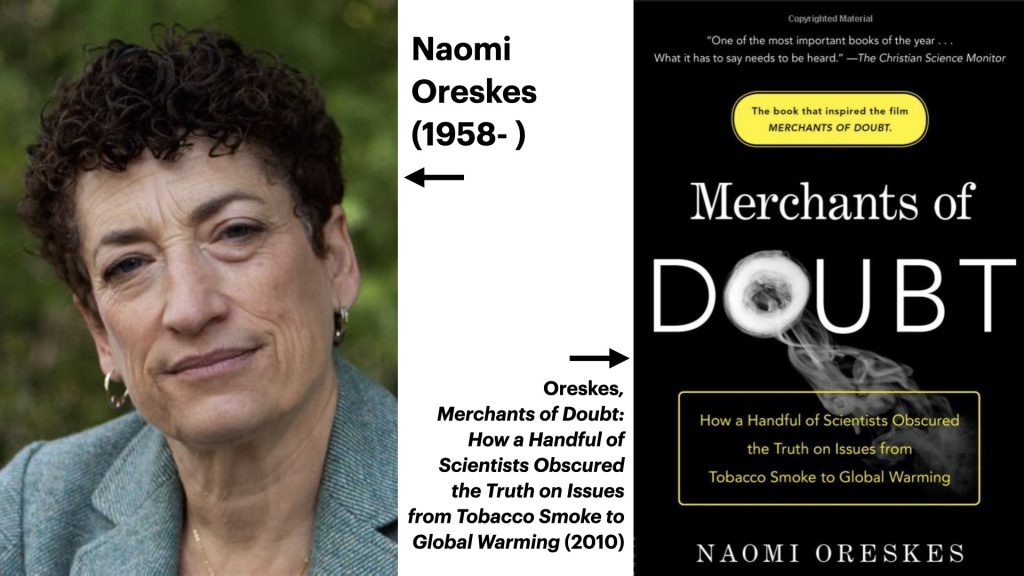

I think to see the real threat to the authority of science you should turn to another historian of science—Naomi Oreskes—and her 2010 book Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming [Bookshop.org, WorldCat]. Oreskes examines what might be called the social construction of disinformation. Here we see not English departments—or sociologists—working against the credibility of science, but large, well-funded corporations and government bureaucracies using the modern signs of scientific credibility to fuel doubt about some pretty well-founded scientific conclusions. Episodes like this, I think, seem to validate some of the ideas of sociologists like Steve Shapin, and show that some of the dynamics he examined in 17th-century England are still true today. Namely, that matters of fact do not exist by themselves, but instead rely on strong reputations, communities, and organizations to maintain them. Just as non-facts, like there is no global warming, rely on strong organizations and signs of trustworthiness for their production and survival.

Thank you very much.